The $10,000 Public Finance Challenge

The $10,000 Public Finance Challenge

The Prize – $10,000 in Canadian funds.

The Claim – That it makes no difference whether a community has its government borrow from or tax resident citizens to fund public expenditures.

The Challenge – Find the flaw that defeats the proof and refutes the claim.

In watching the video do note:

1. That Government does not fund Government.

2. That Government’s deficit is the whole of public expenditures, and not simply expenditures beyond tax revenues.<

3. That taxpayers or resident citizens, and, specifically, the aggregate of their assets, property, incomes, and wealth, fund government or rather public expenditures.

4. That one must examine this aggregate of assets, property, and incomes of resident citizens, or what I term ‘that which funds government’, to arrive at proper and reasonable conclusions in Public Finance theory, and not the finances of an entity that has no such assets.

5. That such an examination reveals that creating or adding to a public debt, adding interest to public debt, and reducing public debt does not alter the aggregate of ‘That which funds government’, if government borrows solely from resident citizens.

6. That every premise of this argument follows reasonably and soundly if one accepts the first premise: “That Government does not fund Government.”

7. My affiliation with a political party has ceased so just ignore the related references.

I wish to present a very interesting but obscure economics idea and proof devised through my inquiries into Public Finance Theory. Having been rather taken with this insightful proof and conclusion, I thought I should share it with the site’s visitors. Because of its profound implications I offer CDN$10,000 to the person able to find the flaw in this startling discovery as all my efforts have failed. Perhaps, one of you shall have that elusive victory. Best of luck to all challengers.

I identified an errant premise in economics that has long marred its theories and practices, specifically those of Public Finance. I argue that modern Public Finance theory presumes that Government funds Government. Yet as we all must undoubtedly concede, the evidence confirms in abundance the very opposite: Government does not fund Government. Government does not provide the funds to pay its bills, does not settle its debts, and does not fund public investments. It never has and it never will. Government has not contributed 1 dime to its expenses since its inception. If one were to account the finances of Government, it would show full indebtedness to the Taxpayer for all funds expended and debts incurred from day 1.

The task of funding government has always fallen to the Taxpayer. So, in order to fully understand public finances, one must apply this long neglected fact. Given that a community of Taxpayers funds government, it is their finances: their combined assets, incomes, property, and money one must examine in order to answer basic questions about funding public expenditures.

In doing so, one easily discovers that it makes no difference whether a community taxes its citizens or borrows from its citizens to fund public expenditures.

To prove this contention I shall examine the question of a deficit. Some think the cure to a deficit, a shortfall in tax revenues over expenditures, is to have the government further squeeze this sum from beleaguered taxpayers and, thereby, dispel all financial troubles. This erroneous cause and solution will have only aggravate the problem.

If a Government has approximately $13 billion in expenditures and tax revenues of about $12.5 billion. The figures may be more or less because governments love to fiddle. However, working with these numbers the deficit would be $500 million.

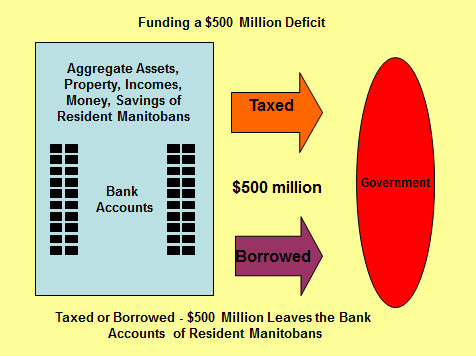

Let us say that the government requires $500 million to fund its deficit. It can tax or borrow the funds.

If it tax, $500 million leaves the bank accounts of resident taxpayers and the deficit is funded.

If the government borrow, strictly from resident citizens, $500 million leaves the accounts of resident lenders and the deficit is funded.

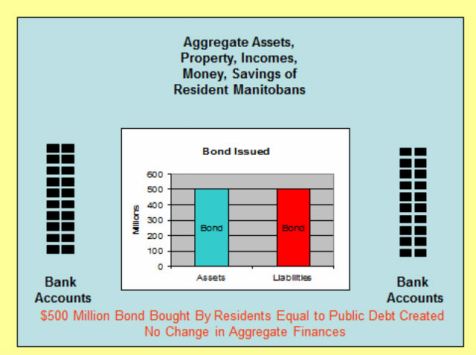

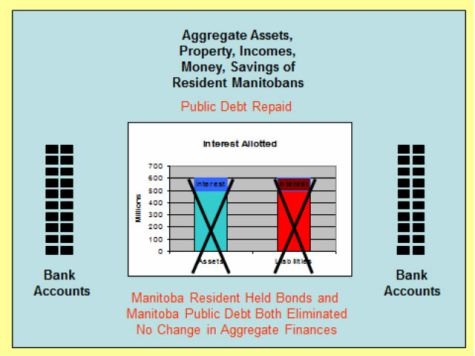

The same $500 million leaves the bank accounts of resident citizens whether taxed or borrowed. However, there is a little extra paperwork with borrowing. A bond of $500 million is issued. This item counts as a public debt, liability, or claim against the combined property, assets, incomes of resident citizens. It equally counts as an asset among that combined property, that which funds government, because resident lenders now hold the bond or paper.

Aggregate Finances of Residents

| Asset |

Liability |

| + $500 million | + $500 million |

So, with an equivalent increase in the size of resident citizens’ assets and liabilities of $500 million, have the aggregate finances of resident citizens’ changed? Not at all.

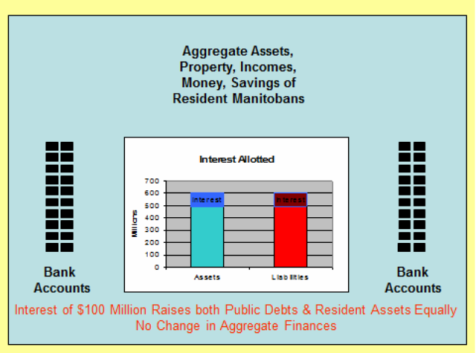

If one were to add interest into the mix say of $100 million, then the aggregate assets of resident citizens rise by $100 million as do their aggregate liabilities.

Aggregate Finances of Resident Citizens (Bond and interest)

| Asset | Liability |

| $500 million | $500 million |

| + $100 million | + $100 million |

| $600 million | $600 million |

So, have the aggregate finances of resident citizens changed? Not at all.

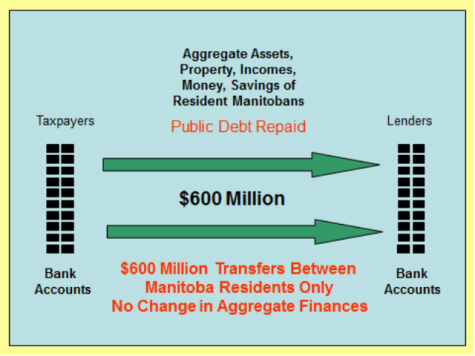

And if the government should decide to pay off the public debt of $600 million by taxing, $600 million is taken from the bank accounts of resident Manitoba taxpayers and moved to the bank accounts of resident lenders. And the $600 million asset of bond and interest is extinguished simultaneously with the equivalent public liability.

| Asset | Liability |

| – $600 million | – $600 million |

| $0 | $0 |

So, again, have the aggregate finances of resident citizens changed? Not at all. All this happens within the wealth of resident citizens. At the individual level there are changes, but not at the aggregate level.

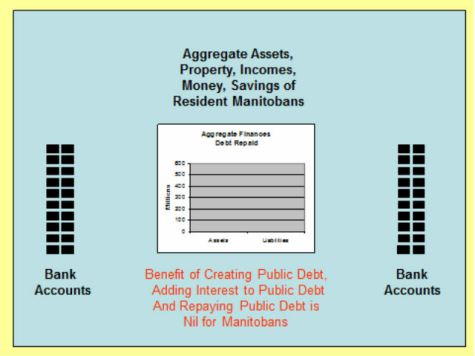

So, as long as we restrict government borrowing to residents, creating a public debt, adding interest to it, and reducing that debt leaves the finances of resident citizens unchanged.

So, as demonstrated, a deficit for the wealth of residents is not a problem.

There is an insight whereof its acknowledgement and insertion into present theory would completely alter the nature and practices of Public Finance and unleash an immediate and perpetual torrent of wealth for the citizens of a jurisdiction implementing it.

Do recall that government does not fund government. Thus, whether taxed or borrowed, all funds expended by government must be considered as financed by deficit. Therefore, the gpvernment deficit is not merely the negligible sum of $500 million, but rather the gargantuan sum of all its expenditures or $13 billion.

By repeating the foregoing example with the numbers altered to reflect the true deficit, the result remains the same. $13 billion dollars leaves the bank accounts of resident citizens, taxed or borrowed. And, in borrowing strictly from resident residents, the act of creating a public debt of $13 billion, adding interest to that public debt, or subsequently reducing or eliminating that public debt does not alter the aggregate finances of residents, or those assets which fund the government.

However, by opting for full Borrowing of all public expenditures instead of Taxation, the government would have to borrow funds instead of eagerly and obnoxiously confiscating them, daily entering the financial markets in pursuit of funds. By turning financial slaves into public bankers the people, the resident lenders, will become the arbiters of which public expenditures are worthy and deserving of funding, and which are unworthy and deserving of rejection.

With the public banker firmly in charge of public expenditures, the government would no longer operate upon the principle of expenditure. Thus, entire programs and departments would be scrutinized and assessed for value and adequacy of returns. The authorities would terminate all politically useful, but dubious, harmful, and barren programs and regulations. Favourable regulations, programs, protections, loans, and payments to politically influential and powerful industries, firms and individuals would be identified and eradicated. If malfeasance and mal-administration should occur or persist, the people will requite neglect and derelictions by depriving government of the means to operate until the agents of waste or corruption have been identified, removed, charged, punished, or imprisoned.

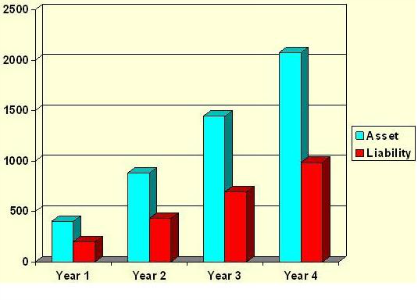

With the petulant and perpetual public banker now in charge, one would expect the costs of government to decline and drastically. Let us say they almost halve from $13 billion to $7.0 billion.

Thus, residents gain an asset of $13 billion consisting of $6.0 billion in cash and $7.0 billion in public bonds held. And residents incur a public liability of $7.0 billion in bonds issued.

| Assets Gained | Liabilities Incurred |

| + $7.0 Billion public bonds held | + $7.0 Billion public bonds issued |

| + $6.0 Billion cash | |

| $13 Billion | $7.0 Billion |

And do recall that the deterrent effect of Taxation would evaporate with its abolition. If the increases in productivity and growth from shedding deadweight costs of Taxation for citizens and firms are calculated and included, the wealth of the province would surge steeply. The return of absconding wealth, assets, able individuals, and productive corporations from formerly light climates of Taxation, the eradication of all constraints upon, impediments to, and distortions of investment, industry, and labour, the elimination of favoured relationships and monopolies that shamefully elevate prices and enhance profits for the select at the expense of the common, liberation from the expensive apparatus of tax preparation and advice, the elimination of onerous and unnecessary regulation, an end to surcharges and constraints upon consumption, an influx of external investors and investment, the end of disparities and inequities in payment of tax, and the erasure of many other unnecessary practices sired by this corrosive instrument should all yield a collective and immense largesse.

It is very conservatively reckoned that the abolition of Taxation, by diminishing costs and spurring profits, would enlarge the assets of resident citizens by at least a further $5 billion per year.

| Assets Gained | Liabilities Incurred |

| + $7.0 Billion public bonds held | + $7.0 Billion public bonds issued |

| + $6.0 Billion cash | |

| + $5.0 Billion eliminated deterrent | |

| $18 Billion | $7.0 Billion |

Hence, the aggregate assets of residents shall rise to $18 billion and incurred liabilities remain at $7.0 billion, leaving the wealth of residents greater by $11.0 billion. Dividing this figure by the population of the province leaves the increase in wealth of every resident at approximately $10,000 for every man, woman and child, or on average $40,000 per household, in just one year.

If this is agreed, then it is easily conceded that Taxation, a penalty, and Borrowing, an inducement, possess little equivalence between them as a means of raising funds for public expenditures. Taxation bears immense costs in deterrence and government squander that disappear under Borrowing.

So why does a community tax with all its inherent and punishing costs to fund public expenditures when it can borrow, escaping these financial ills, and unleash great wealth for its citizens?

This is our $10,000 challenge: that it does not affect the combined assets, property, incomes of resident citizens, i.e. that which funds government, whether the community borrows from or taxes its citizens to fund government deficits. So submit the flaw in our reasoning and gain the prize.

If unable to discover the elusive flaw in our reasoning, perhaps the idea will be of some service in rendering the stagnant field of economics once again fertile.

Certain Questions Repeatedly Arise with the Reading of the Foregoing Proof.

I have provided answers for the primary queries below. If no answer is found for your question or an answer unsatisfactory, please do provide the question or nature of the inadequacy in a comment and I shall respond as soon as possible. If it should fatally wound the proof, then you shall receive the promised reward of $100,000CDN.

How can a community borrow without end to fund public expenditures?

An individual, or firm, may borrow as much as he desires as long as the assets purchased or created with the borrowed funds exceed all liabilities.

Were a community to abolish Taxation and begin borrowing all of the funds needed for public expenditures, as long as assets exceed liabilities, those within need not fear financial calamity.

With the abolition of Taxation 2 important obligations would come into play:

One: that government, the community’s agent in public expenditures, will now have a capital charge.

In the present, when the community through its government furnishes a good or service, one is never sure the money expended in the effort bears a calculated return, a return that surpasses all costs. With Taxation abolished and the imposition of a capital charge, the government will have to garner at least that rate of return on public expenditures.

Two: the government will have to face the community every time it requires funds.

Under Taxation, a government may take the funds and do as it pleases. With its abolition, government will learn very quickly not to mistreat its perpetual banker. The people, converted from financial slaves to public bankers, shall directly determine legitimate public expenditures.

These 2 factors will create a revolution in how government operates.

The costs of government would certainly contract.

Wasteful expenditures would decline rapidly as the return on any public expenditure must exceed the capital charge.

There would be no more tax collection, no subsidies to favoured industries, firms or persons, far less corruption, far fewer regulators, far fewer and much smaller government departments, far greater controls on enduring expenditures, the use of service fees to curb abuse of public resources, etc.

In a nation with annual public expenditures of $300 billion, savings of $100 billion could easily be had.

And what would happen to the other side, to the financial assets of all citizens and corporations:

Taxation is a deterrent. It deters one from doing what he would normally do were there no taxation. Without this burden, there will be all lot more worthy economic activity and far less of the other kind.

There would be no taxes to pay and no papers to file, no taxes in the prices of goods, no tax distortions or burdens in the labour, financial and commercial markets, far less needless regulation and interference, more open and competitive markets, few inequities.

In my home country of Canada, with savings from annual public expenditures combined with the removal of the Taxation deterrent, over 4 years, I estimate very conservatively the accumulation of $1 trillion in wealth with the abolition of taxation.

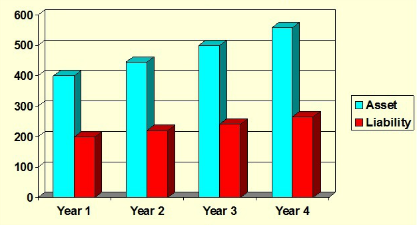

| Year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Cum. Community Assets | $400 | $880 | $1443 | $2076 |

| Cum. Community Liabilities | $200 | $430 | $694 | $986 |

In the US, one may multiply everything by 9 or 10, which means a conservatively calculated increase in wealth of about $9 trillion in just 4 years.

Over those 4 years, the community through its government will acquire a much greater financial debt, but with that debt it will acquire accruing assets at least double that burden.

If a corporation were able to create $2 or $3 dollars of accruing assets for every $1 of accruing liabilities, who would not readily lend to such a corporation?

What is this Cost and Benefit Analysis that Government would then perform?

It is said that public expenditures do not add to the wealth of a nation. I disagree.

The problem is that with Taxation government may simply take the money and do as it pleases. One does receive some valued public services and goods, often at the maximum possible cost, but one also tends to receive many more of the worthless variety.

How might the government assess the merits of a public investment creating wealth in a community?

Let us say we have a paved road in a community. It has a big hole in it. The vehicles using this road hit the large hole leaving them severely damaged. There is a huge cost to the community’s residents in mending damaged vehicles, but not enough damage to any one vehicle to induce the owner to fix this hole.

Say the cost of vehicle repair is $3000 and the cost to repair the hole is $6000. Say 30 cars are damaged causing $90,000 in increased transportation costs on a weekly basis.

How does the market system fix this hole when no one person will pay to fix this hole?

Now, what is the daily cost of leaving this road unrepaired for the residents of that community or what is the benefit of repairing that road for the residents of the community?

It looks like the cost is $90,000 to the community in not fixing the $6000 hole.

So a $6000 public expenditure will yield a $90,000 return for the community.

Such analysis will become the future of public finance.

Broken Windows Fallacy

Some have argued that the ‘broken windows’ proposition, or really any economic activity that leads to increased GDP, is a great benefit for the community and its residents. This is erroneous thinking.

In the previous question, the funds that the vehicle owners must hand over to the garage owners is disposable income, or profit if you will. It is $90,000 per week that could go to save, invest, retire debt, or consume. It is money above all costs of operations for businesses and households.

With the hole in the road, those businesses and households must divert these profits to mending damaged vehicles. Their costs of living or of operating have risen. But the funds forgone are not pure profit to the garage owners, who must buy parts and materials and perhaps hire new staff to meet the increased demand for their services. The resources of the community in labour and materials, diverted from worthy economic pursuits to unworthy economic pursuits, result in greater costs of living and a poorer community.

Now imagine the Keynesian advocating for new, needless, and excessive government regulations that increase costs for businesses. Firms must hire new staff for their manufacturing operations. The cost of manufacturing goods rise, forcing consumers to pay more or businesses to accept less for their products.

It’s no different from employing a fellow to dig a hole in the morning and fill it up in the afternoon. The costs of production rise without any increase in output or supply. Demand rises for the goods of the community because a fellow has a job. However, he adds nothing to supply, meaning he is a burden rather than a benefit.

Wind energy follows exactly the same course. Labour, investment, and materials diverted from producing valued goods to producing worthless goods greatly harm the finances or inflate the costs of a community. The costs of such ventures are immense and the return a negligible and unstable increase in energy supply.

Public expenditures undertaken by the Government can produce valued goods. However, in a climate of Taxation, they rarely do.

How shall the Government repay Resident Lenders the Loaned Funds when it apparently has not the Means of doing so?

Government does not pay its debts. It does not fund public expenditures. The government is in deficit to the full extent of its expenditures, not just to that amount not covered by Taxation revenues. Were one to account the finances of government, it would reveal a shocking indebtedness to the taxpayer of the sum total of expenditures from its inception. Government in its long history has not and nor shall it ever contribute $1 dollar to settling public debts or funding public expenditures as it generates none of its own revenues. The task of funding public expenditures or settling public debts has always fallen to the taxpayer.

Given that the community of taxpayers funds government and settles public debts, it is their finances one must look at and examine in order to answer basic questions about funding public expenditures.

An individual lender shall always receive their promised funds of interest and principle upon demand. The community via its government shall simply exchange one lender for another, just as any financial lender or bank, which never has to make good on its aggregate IOUs. The liabilities of banks rise through the years. Individual lenders are paid off by the bank exchanging one lender for another. And so it would be with public borrowing.

Resident lenders will be repaid with the funds borrowed from other resident lenders. Liabilities will rise, but the community’s accruing assets will always outpace them by 2 or 3 to 1. If the community debts amounted to $1 billion, know that those debts have sired assets within the community of at least $2 or $3 billion.

Would It Ever Be in the Financial Interest of the Community to Reduce its Outstanding Debts?

The answer is clearly no as the provided proof demonstrates.

Theoretically, at some point in the future, the community via its government could collect taxes in the amount of all debts and interest from the community, i.e. the taxpayers, and simply hand the collected funds right back to the community, i.e. its lenders, erasing the acquired community government debts and assets.

So, the community via its contracted agent, the government, would collect X principle and Y interest from the community’s taxpayers. It would take in all outstanding IOUs and cancel them, eliminating in one stroke both the community’s public debts as well as the assets held within the community by its resident lenders. It would then hand X principle and Y interest gathered from the taxpayers back to the resident lenders. The result of cancelling both debts and assets and the gathering and return of the equivalent funds would be nil since the aggregate financial position of the community and its residents is unaltered in the transaction.

All debts and assets sum to nil before the transaction and again after the transaction. The financial benefit of paying down the debt for the community is nil. However, the costs in using Taxation to collect funds to retire the community’s debts are immense in government squander or, at least in this one instance, in its deterrent effect.

It is similar in circumstance to a person or firm selling an asset yielding 50% to settle a debt with an interest charge of 0%. No rational person would ever undertake such a sale.

Thus, the community will NEVER retire any of its outstanding and accumulating debts.

Doesn’t Ricardian Equivalence Vanquish the Proof?

Ricardian equivalence dictates that taxpayers will have to save money in order to retire the debts incurred on their behalf for public services.

Now I have stated in the previous question that a community could tax to pay off its debts, but that it never would because the cost of doing so would be immense and the financial benefit nil. Thus, there will be no debt retirement. The individual lenders shall be repaid by exchanging one resident lender for another, but the community debt once issued shall circulate forever. So Ricardian equivalence does not apply to this idea.

Secondly, as explained above, the wealth generated in limiting government to expenditures of confirmed value and in removing the great deterrent of Taxation upon all worthy economic activity will be incredible. When a community’s accruing assets outstrip its accruing liabilities by at least 2 or 3 to 1, as will certainly be the case, then Ricardian Equivalence as a problem evaporates.

For a full discussion go HERE

Is this MMT or Modern Monetary Theory?

No, it’s not MMT.

With MMT the national government would just drop off its debt papers or bonds at the local Fed bank and have its account credited there for the funds. It is equivalent to a government creating as much money as it pleases as they did in the old Soviet corpse or in Zimbabwe. There will be no constraint upon public expenditures. With profligate expenditures and a great deterioration in the value of the nation’s currency, people should quickly find other forms of money or other currencies to use.

The Euro is a fascinating instrument since one government has little control over the actions of the European Central Bank. Euro money are the same throughout the nations using it. It is free to move through the member banks. A cheque drawn on a Greek bank and cashed in Germany will end up at the ECB for payment. The Greek Central bank must have the Euros to transfer to the German Central Bank. Greek Government bonds will not be sufficient for payment unless all other Euro members agree to it. So the Greek Government may have to enter the financial markets to borrow Euros at market rates to complete the transfer.

The community will have to borrow directly from resident lenders for needed public expenditures. And resident lenders may not wish to lend to a government known to squander large sums of money. With such constraint exercised, one may easily expect that public expenditures will decline to a fraction of their former size, making the community government far more productive and the community that much wealthier.

MMT, like present day Taxation, has no check upon profligacy among national governments. Public borrowing possesses such a means and a very effective one.

Free Rider?

The question of a free rider disappears. There are no free riders or all are free riders. The community will decide worthy public expenditures based upon a cost and benefit analysis. Briefly, the expenditures will pay for themselves. Funds borrowed for public expenditures at 5% must generate a return of at least that amount. If not, the expenditure is delayed until conditions change.

The community only requires the funds to make these expenditures. It offers a market interest rate. Those enticed will lend. Those with better returns or uses for their money will not. When an erstwhile lender finds a better use for his money, he shall present his bond to the government for payment, and another lender with lesser financial prospects shall fill the void.

Lend for a return, or don’t. None is forced to cede funds. Those that do are properly rewarded. The public expenditures will pay for themselves in yielding financial returns greater than all costs. The problem of the free rider vanishes.

The failure of your proposal is that it does not create incentive to rein in spending as you suppose. To start, it must be accepted as axiomatic that all individuals in the community are rational and primarily self interested. If you do not accept this axiom, then any economic theory can be proven and the exercise is pointless.

There are three groups who must be considered in your proposed system: government employees, investors and other citizens. Begin with a proposal for repairs on the Trans-Canada highway (any capital project would be fine). The government employee group would benefit from this proposal, in that jobs would be created or sustained for them and civil servants in charge of the project would gain power and prestige (an important non-monetary reward). The other citizens would benefit, in that some of them would receive government contracts and profit from the construction, and others would benefit from improved transit. The group who must be convinced are the investors. For them to invest their money, they must receive a competitive rate of return. This then becomes the deciding factor for any government project that offers some public benefit: can investors earn a market rate of return on their money. In this case, they can. The government will offer to issue bonds at the market rate to pay for the project. As the government has no revenues, interest on the loans will be paid by further borrowing. The government offers bonds, and the project proceeds.

The fatal flaw is that I did not quantify the costs or benefits of the project in the above, and was able to make the project attractive for all parties anyways. As long as the public benefit is zero or greater, and the government employees get at least some additional money or power from the deal, the government and the other citizens want the project. The investors care about neither of those things, but instead focus on whether they can make money on the deal. The debt only system divorces the benefit of the project from its cost. The government will offer investors whatever return is required to entice them to invest. It makes no difference to them, as they have no revenues and will be borrowing whatever the interest payments end up being. Ultimately, at some point investment funds will dry up. Either investors will begin to doubt the government’s solvency or they will simply run low on money. When this happens, taxation must occur.

There are three ways in which wasteful spending could be prevented. First, lenders could refuse to lend to projects whose social net benefit was not positive. They have no incentive to restrict themselves in this way, however. The projects to not generate revenue sufficient to cover their costs, typically because they are public goods whose social benefit is not easily quantified and apportioned. National defense is the standard example, in that it is difficult to quantify the value of an army to any one individual taxpayer. If they could be easily monetized, the private sector could already provide them and government involvement would be unnecessary. Given that, investors do not care about the economics of an individual project, but only about the prospective return on the bond and the risk of government default. Whether the project has a positive social return is not directly reflected in the government’s finances, and so is irrelevant to their calculations.

Second, the government could limit itself. It will not do so, because its members primary incentive is their own job security and advancement. If the government were capable of limiting its own expenditures, it would do so under the current system.

Finally, the other citizens could protest wasteful government spending. Currently, they have incentive to do so because they pay mandatory taxes. Remove the element of coercion, however, and they have limited reason to care. For your system to work, taxpayers must believe that taxation will not be reimposed. Otherwise, Ricardian equivalence applies. If taxation will not be re-introduced, expenses can be deferred indefinitely. What incentive does a citizen have to care about a debt she will never have to pay?

That is not the only problem with your proposal, but it is a simple one. By removing mandatory participation in government funding and basing it solely on investment, with perpetual delaying of debt repayment, the connection between costs and benefits is severed. As a result, there is no reason to limit public spending.

Hello Tom,

I did read through your comment. You argue that since one can satisfy all parties, then any project no matter what the cost or benefit may proceed, giving favour to certain parties.

Now I must take issue with your assertion that you can satisfy all parties. There will be a large number of competing firms offering a better rate for the project than the government outfit. The owners and their employees will not be pleased to see projects for which lower bids were tendered awarded to those offering elevated bids. Nor will their family members be much pleased with the outcome. Existing bondholders and potential bondholders wishing to subscribe to the lucrative issue with its elevated returns will not be pleased when their offers of funds are rejected in favour of those more influential, jeopardizing not only previous issues of debt, but also future subscriptions. So I do concede there will be a few beneficiaries. But the few beneficiaries will be greatly outnumbered by all those prevented from getting in on the fine deal. And the disgruntled many will certainly be reluctant to lend to an organization that would thrive with Taxation, but perish without it.

Were I a member of that community, I would cease lending a dime to that community until someone went to jail. And I might also start dumping all holdings of that community’s debt if the debacle should endure. I shall let you deal with this before moving on.

You have two primary issues that more or less render your idea invalid.

The first is that government, in and of itself generates no revenue. Under your idea, it would exist in perpetual debt (Which I will grant is no change from the status quo), taking a new loan to cover the old loan because aside from taxes there aren’t any revenue sources large enough to handle the workload.

More than that, public works such as roads and schools aren’t “fire and forget”. Maintenance costs require a steady stream of revenue, and constantly hounding after new loans isn’t going to create the capital flow necessary to continue that upkeep.

Secondly, emphatically, while there’s a fool born every minute, those who run our largest financial institutions are only interested in cutting a check if it lines their own pockets (Which really, despite my dirt-poor status, I recognize as business sense.) and trillions of dollars of unsecured debt is just never going to be a sound investment.

But for the sake of argument, let us assume there is a firm, or even (however unlikely) that there are competing firms offering to operate this business.

What happens when the balance comes due? The initial, plus the interest?

If you strip away taxes, there must be some means by which our government builds revenue. Otherwise, even under the best of conditions, we’ve no hope of addressing the deficit.

So what assets does our government hold to leverage as means by which to either generate revenue or leverage as collateral for their debts? Do you propose that we simply take another loan to pay the first? Because if that is the case what we will find is that the trillions of dollars in unsecured debts will become trillions of dollars plus interest of unsecured debts that we can simply take a loan for as long as some rube is willing to believe that “this time will be different” speech we hear every four years.

The flaw isn’t in a mathematical proof, I would agree there must be more efficient ways than the current tax systems. The flaw is in simple human nature. You aren’t addressing the one problem that truly needs to be addressed – When do we stop spending money we don’t have?

Nice little thought exercise though!

Hello Richard,

Well, you are correct and absolutely when you state that government has no means of generating funds. Since this is so, the government presently exists in perpetual debt. Its debts total up to the whole of its expenditures from the point of its inception. It is as you say a debt laden institution. Its not paying the money back that its taken from the taxpayers all these years, but it is still a debt laden institution.

You remark that borrowing to fund a road or its maintenance does not generate a steady stream of revenue for the government. True. But neither does Taxation. Under either system, the road doesn’t pay the government a steady stream of revenue. So the returns generated by the public investment in the road and its maintenance will find their way into the pockets of those that actually fund government, the resident taxpayers or the resident lenders. They shall reap the rewards of such an investment. Not the always debt laden government. And as long as financial benefits to the residents exceed costs, then the community is wealthier. If not, then the community is poorer. And the collateral for the community’s debts will be found in the combined property and assets of residents, as it is now under Taxation. The community’s liabilities will grow through time, but with the enormous wealth generated by the abolition of Taxation, the community’s assets and property held by its residents will grow at a rate of 2 or 3 to 1. If there be $10 trillion in community debts, know that there will be $20 to $30 trillion in assets generated within the community by those debts. And who would not lend to such a wealthy corporation?

When do we stop government freely and imprudently spending the money of others? When one forces government to face its perpetual and petulant banker every day.

Economart,

I find this proposed solution interesting, and I believe theoretically it would work. That is, in theory it is not flawed, but in practice it would run into problems such as depreciation, the physical assets the government is using as collateral, are decreasing in value and thus at some point the government will find itself unable to offer sufficient collateral to secure additional loans as it can not use the bonds the community is holding as an asset to secure additional loans.

Hello Joseph,

The collateral the Community government uses to back the bonds issued in a system of Borrowing are not the depreciating assets of those public investments made within the community, but rather the combined property and assets of all the residents within that community. Its just the same as it is under Taxation. With a community’s residents greatly enriched by the abolition of Taxation, the community’s credit will expand exponentially.

Economart,

I believe your “balance sheet analysis” of the simple debt-financing scenario you present is correct; that is, the combined net worth of the “community” and the “government” remain the same under debt- versus tax financing. However, I think an analysis based on this simple, arithmetic reasoning ignores various considerations that explain the seeming challenge. Firstly, debt financing (interest expense) increases project cost. While combined net worth across balance sheets (community and government) may remain the same in both scenarios (debt- versus tax- financing), overall societal welfare may decline under the debt-financed scenario as society pays more for a good or service (e.g., a bridge) than it otherwise would pay through tax- financing. This may impose a cost on society. Secondly, if as your challenge states, the debt-financed government solely borrows from the community to finance expenditures, then the debt-financed government must continually issue new debt to cover interest expense on previously issued debt. Project cost continuously grows as interest expense continues indefinitely (although approaching zero in the limit). This imposes an increasing cost on society. Additionally, this debt-financed government must now be infinitely lived so that it may continuously issue new debt to cover interest expense on previously issued debt. Alternatively, a tax-financed government theoretically need not be so infinitely lived. A longer-lived government likely comes at greater cost than a shorter-lived government and a solely debt-financed government may entail greater costs than a solely tax-financed government. Finally, while your debt-financed government scenario seemingly considers the increased costs of infinitely financed projects and an infinitely lived government, it seems to dismiss these costs in a somewhat flawed way. Namely, the challenge states we can eliminate infinite life costs and concerns by collecting at some future point taxes equal to the amount of interest expense outstanding, and by then returning that amount to the community. However, we now have a government that uses both tax- and debt- financing to fund expenditures and we violate a fundamental assumption of your challenge – that there exists a government that that solely borrows from the community to finance expenditures.

Hello Jim,

Thanks for the agreement on the proof. A lot of people have a hard time seeing, let alone accepting its conclusion.

You argue that a project’s cost will now rise because interest has become a factor. That is true in a way. But money does have a temporal cost in that dollars invested today generally will bring returns. Some investments are safer and less rewarding than others. This cost works its way into the decisions and actions of investors, firms, bankers and individuals. We calculate daily the costs and benefits of our proposed expenditures. We analyse them for returns, labouring at making benefits exceed costs. What you say is quite correct. The interest rate will factor in this time component for money. Those projects garnering elevated returns with commensurate risk should proceed.

Government presently performs no such analysis. It has no means of determining the value of a public investment, not because such a means does not exist, but because it has never had to develop and utilize them under a system of confiscation. Bereft of confiscation, Government will be forced to examine every expenditure for its inherent costs and benefits to the community it serves. This capital charge will purge the government of all those politically valued but essentially worthless public expenditures. This charge will render a great service in that those investments for which returns are elevated will proceed and those with dubious or inferior returns shall not, creating a far wealthier community.

You are correct that the costs of government expenditures with the interest charge will accrue throughout the ages. However, so shall the returns generated by these expenditures. A school built and staffed today has a cost. And it has a benefit in that the children educated within its walls will earn incomes exceeding those not educated. Yes the debt and accruing interest in that community shall fly forever. But so shall the returns in elevated incomes fly forever with the wealth and property earned by the educated persons passed on to future generations.

Now suppose a man must pay some tax on income. He would rather settle a debt on a credit card with an interest rate of 30%. The government will take the money and put it into some public investment of which the costs are known but the benefits are not. He can generate a return of 30% on repaying the debt. Can the government also generate such a return? Such a scenario is never accounted in a system of Taxation. It is in a system of Community borrowing. Would it not be best for the fellow to pay off his debt and ignore the return of say 5% generated by a government bond?

I think you misunderstand my criticism. It is not that projects will necessarily be pursued inefficiently (passing over low bidders or financing at higher rates than the market demands). It is that projects which should not be undertaken at all, because their cost outweighs their social benefits, will be undertaken. This is because the infinite horizon for debt repayment divorces costs from benefits. Whether the bidding for contracts for these projects is honest is another question, and I see no reason why it would be better or worse than under the current system.

Hello Tom,

What happens in the present when a community or nation such as Greece does as you propose? What happens when a rather reckless borrower turns to the financial markets for funds for some dubious project that offers little in the way of benefit to the populace but great benefits to those funding and undertaking the work? Lenders are very cautious people. They want to know that a borrower possesses the assets necessary to satisfy their demands for repayment. When lenders feel repayment is impaired by the heedless deeds of their borrowers, funds become scarce and interest premiums become the norm. So why would a community of citizens allow certain nefarious and malfeasant persons within the government to imperil the value of their property and wealth for the benefit of a few sordid characters?

We all know how the financial markets deal with those persons or entities that cannot repay their debts. Credit is forbidden and all transactions occur on a cash only basis. Imagine the financial ramifications of a community forced to impose Taxation on its residents to fund public expenditures when no others do?

Regards,

The flaw: one line

Guaranteed borrowing implies a willing lender.

The flaw: detail

Via taxation a government, if ideal, produces public facilities of equivalent

cost. It can do so because the taxation contract ensures the presence of the

requisite funds. In borrowing (by definition not mandatory) there is no such

contract and as such any works undertaken by the government are liable to

fall short of completion (or even decent progress) depending on unwillingness

of the lenders (the citizens). Therefore, the above model is flawed because

of lack of guarantee.

The lack of guarantee for completion of any piece of work undertaken can become

self-fullfilling. This is easy to see a lender will not invest in something he sees as high risk

and the government has no way of offering guarantees.

Hello Xule,

Sorry to have taken so long to respond. It has been a busy day.

I did read through your comment. You argue that one would never lend to a borrower that could never repay the loan.

There are 2 elements in my reply. The first is who the borrower actually is. The second centers upon repayment.

Firstly, I said on the main page and elsewhere that “All my work forms its foundation in one self-evident truth, that government does not fund itself. It does not pay its bills. It does not settle its debts. It never has and it never will. That task has always fallen to the Taxpayer. In order to fully and properly understand how Public Finance works, one must apply this little appreciated fact. Given that the community of Taxpayers funds government, it is to their finances on must look and examine in order to answer rudimentary questions in this area of study.”

So it is the citizens of a community that are responsible for settling the debts incurred for public expenditures. It is their assets that form the collateral for all debts incurred by the community through its agent, the Government. The funds with which to repay the debts rest in their hands as they do presently with borrowing in combination with Taxation.

On the issue of settling those debts, I never said that the community could never repay its debts by Taxation. I said that the community would never settle its debts because the cost of doing so is immense and the financial benefit is nil.

“Would It Ever Be in the Financial Interest of the Community to Reduce its Outstanding Debts?

The answer is clearly no as the provided proof demonstrates.

Theoretically, at some point in the future, the community via its government could collect taxes in the amount of all debts and interest from the community, i.e. the taxpayers, and simply hand the collected funds right back to the community, i.e. its lenders, erasing the acquired community government debts and assets.

So, the community via its contracted agent, the government, would collect X principle and Y interest from the community’s taxpayers. It would take in all outstanding IOUs and cancel them, eliminating in one stroke both the community’s public debts as well as the assets held within the community by its resident lenders. It would then hand X principle and Y interest gathered from the taxpayers back to the resident lenders. The result of cancelling both debts and assets and the gathering and return of the equivalent funds would be nil since the aggregate financial position of the community and its residents is unaltered in the transaction.

All debts and assets sum to nil before the transaction and again after the transaction. The financial benefit of paying down the debt for the community is nil. However, the costs in using Taxation to collect funds to retire the community’s debts are immense in government squander or, at least in this one instance, in its deterrent effect.

It is similar in circumstance to a person or firm selling an asset yielding 50% to settle a debt with an interest charge of 0%. No rational person would ever undertake such a sale.

Thus, the community will NEVER retire any of its outstanding and accumulating debts.”

The residents of the community through the debts incurred will garner assets at least double or triple those of its accruing liabilities. So who would not lend to such a prosperous community? Who would not lend to a corporation generating a return of 100% or 200% on invested capital?

Regards,

Economart

Interest rates are endogenous.

Pay up

So?

The claim that the cost of borrowing from its citizens is zero, in the way it has been proposed, is equivalent to saying that taxes to fund the government’s expenditures may be substituted with borrowing from the citizens. At the center of the argument is the idea that, given that the government doesn’t have funds of its own, if the government borrows, society creates a liability and an asset of the same size.

There are two flaws in the argument:

1. The type of lending proposed will not occur in the absence of a commitment

of the government to tax.

2. The assumption that the asset=liability is only true under very specific

conditions.

Let me begin by formalizing the setup and the argument. I will keep it as

simple as possible but you will have to excuse the length of this post.

Before I start this, let me highlight what, in this context, is

the distinction between taxes and borrowing/lending (its obvious in “real life”

but we need an actual formal distinction): taxes are coerced while lending is a

choice made by citizens/individuals.

Setup: There is a government that needs to fund a public good. The cost of

this good is T and it will generate, let’s say, a flow of services g to every member

of the community in every period. Note that I am assuming that the government

is providing a public good an therefore there is a need for a government to begin

with (the whole argument is about how the funds from the community should

fund the government). Because we are talking about lending and borrowing,

we need more than one period. Let’s assume, without loss of generality, that

there are 2 periods. There is a community that generates/receives income Y(C,t)

in periods t = 1; 2. The argument you propose is the following:

Scenario 1 (taxes): The government taxes the community by amount T in

the first period and produces the public good. Thus, the community receives

Y (C,1)-T disposable income and g services in the first period, while it receives

Y (C,2) disposable income and g services in the second period.

Scenario 2 (borrowing): The government borrows T from the community in

the first period and produces the public good. Thus, the community receives

Y (C,1)-

Hello DiegoA,

I see where you are going with your argument, so I am going to ensure that you understand one crucial point that is central to this idea.

As stated in my most recent post: https://www.economart.ca/how-will-a-community-repay-its-public-debts-without-taxation/

Do recall that the government does not furnish the funds with which to settle its debts. Government does not pay taxes. It does not fund public expenditures. The government is in deficit to the full extent of its expenditures, not just to that amount not covered by Taxation revenues. Were one to account the finances of government, it would reveal a shocking indebtedness to the Taxpayer of the sum total of its expenditures from inception. Government in its long history has not and nor shall it ever contribute $1 dollar to settling public debts or funding public expenditures as it generates none of its own revenues. It conducts the nation’s public business for the benefit of the nation. The task of funding public expenditures and settling public debts has always fallen to the Taxpayer.

Given that a community of Taxpayers funds government, it is their finances: their assets, incomes, property, financial instruments, and money, one must look at and examine in order to answer basic questions about funding public expenditures.

Government does not have any finances. It has no pile of money. If funds nothing. Its records consist of an endless stream of “money expended” and next to it “invoice to the taxpayer.”

You are again making the error of attempting to analyse public finance from the finances of an institution that is fully reliant upon others for its funds. You can read about this in my post “Who or what Funds Government.”

When you accept this premise, all that I have said follows naturally, reasonably and logically.

I hope that helps.

Regards,

Economart

My previous comment seemed to be cut short. I would be happy to email you the whole discussion.

As I see it, the flaw in your argument is the “Tertium non datur” fallacy: either taxation or borrowing, and no other alternative.

There are many “private communities” with a government-like entity that is supposed to provide for and take care of the public parts of the community (roads, utilities, first-aid facilities, etc.) yet does not borrow from the members and has no power to tax them. Instead, it demands a periodic contribution. Members who do not think they get value for their money are free to leave, but if they do, they cannot take an IOU from the community with them. In paying their contribution they get no financial asset.

Why do we not find private communities that do not adopt your “Borrow, do not tax”-scheme?

Because, private communities are dynamic entities. They cannot count on always being able to find a new lender to repay a previous creditor. People can leave without being replaced by others (in particular, by others who insist on the same level of the same kind of public service or amenities). So, they adopt a pay-as-you-go-and-take-it-or-leave-it scheme.

The crucial issue is the relative cost of leaving a community. On the one hand, if that cost is high, the government has much power to tax. If it is low, it has little power to tax. On the other hand, if the cost of leaving a community is high, then the government can easily borrow from its subjects. If it is low then borrowing exposes the community to the risk of having to pay former members without having the guarantee that they will be replaced by new members of the same or higher “financial capacity”. Only when the cost of leaving a community is prohibitive do we find the conditions of your “If taxation pays for it then borrowing can also pay for it” (provided, of course, that your community never loses the trust of large segments of its population).

Hello Frank,

The proof concentrates upon Taxation and Borrowing. There are certainly other methods out there to fund public services. To know the best way to fund them is not really my focus. If Borrowing should replace Taxation, public finance must resolve what goods are worthy of public investment and what are not, what public investments are worthy and what are not. It will all come down to cost and benefit analysis. Until then, all that I say is that wherever government taxes, it is better of borrowing from its citizens.

That is about the best that I can do. Sorry.

Economart:

Many years ago a very poor assumption established itself in economics and, specifically, public finance. It was accepted without proper investigation that Taxation is the best means of raising capital for public expenditures. I argue that it is not and never has been.

Ed Griffin: I totally agree. I have long been an advocate of voluntary funding.

Economart: An individual, or firm, may borrow as much as he desires as long as the assets purchased or created with the borrowed funds exceed all liabilities. Were a community to abolish Taxation and begin borrowing all of the funds needed for public expenditures, as long as assets exceed liabilities, those within need not fear financial calamity.

EG: “As long as assets exceed liabilities” is the critical phrase. Governments are notorious for failure to complete projects within budget and even more so for failure to produce positive cash flos from their projects. The value of assets often is overstated in the books, and it is not unusual for them to remain encumbered by greater debt than their true market value. Sophisticated investors would hesitant to lend money to governments for profit-seeking ventures without knowing that their loans are backed, not merely by tangible assets, but by the taxing power of the state, which can service the debt in spite of negative cash flow and business failure. Furthermore, most government budgets are for non-asset expenditures, such as legislatures, courts, police, firefighting, wars, foreign aid, research grants, and welfare, to name a few. I am not aware of any sector of the investment community that would lend money for these projects unless backed by the taxing power of the state.

Economart: In the present, when the community through its government furnishes goods or services, one is never sure the money expended in the effort bears a calculated return, a return that surpasses all costs. With Taxation abolished and the imposition of a capital charge, the government will have to garner at least that rate of return on public expenditures.

EG: I agree that this is a problem with the present system when applied to potentially profit-making ventures, such as roads, airports, seaports, and the like, but those are not really proper functions of the state anyway. They have little to do with protecting life, liberty, or property, which is the sole, legitimate purpose of the state. If government-owned projects can be profitable, they should be left to the private sector. There is enough temptation for corruption in public office without adding money-making ventures to the mix. Beyond that, it is unrealistic to assume that sophisticated investors will lend money to the state for its proper functions, because those have minimal marketable assets and totally negative cash flows. This is the fatal flaw in the theory.

But the theory still has much value in it and, with only a slight modification, it can become bullet-proof. Perhaps this can be the topic of future comment, if you are interested, but that is why I advocate a completely voluntary system of citizen support of the state through donations and pledges. If we can fund the Red Cross, cancer research, and even public broadcasting voluntarily, we certainly can fund defensive armies and fire departments that way. Not everyone will donate, but enough will do so to pay the bills. If the state must justify its activities in periodic fund-raising drives, there will be very little money donated for aggressive wars, foreign aid, and forced vaccinations. Many problems relating to bureaucratic mission creep would be automatically solved if citizens could allocate their donations to specific activities and works. I assume that was one of the advantages you anticipated with voluntary lending but, for the reasons stated previously, could never materialize. There is no such problem with the concept of voluntary donations and pledges. The only barrier is that it is a new idea for most people, and they will have trouble, at first, appreciating the power of volunteerism. But, in practice and theory, the concept is totally sound.

Hello Edward,

John mentioned you would be dropping by.

I read through your comments. I think there is a slight misunderstanding regarding several matters that stems from looking at this as more than a revenue question in public finance. I am only interested here in how the government fills up its money bag, not really how it disburses public monies, though this does enter the discussion as a secondary consideration.

We agree on the issue of Taxation and voluntary funding.

When I speak of assets and liabilities, I am speaking of the assets, that is the property, incomes, financial instruments held by citizens, that fund government and the liabilities claimed against those assets. Remember what I said, Government does not fund government. It generates no money with which to pay its bills or settle its debts. It merely takes. It is not a Sears store. The property, assets and incomes of the residents of a jurisdiction fund government.

So if you add a community debt of $10 million to the claims against the assets of community residents whilst also adding an asset, the same $10 million bond, to those same assets, specifically those of its lenders, then you have not changed the finances of those who fund government in the aggregate. Add in interest requires you to add to both liabilities and assets. Reducing the public debt means you reduce simultaneously both the assets and liabilities of community residents. In each case the finances of those who fund government is unaltered. So why pay down a debt when the wealth of the community is unaltered in the transaction? Why raise funds by Taxation when raising funds by Borrowing does not change the aggregate finances of the community?

I don’t say that a community cannot have its government tax to raise funds for public expenditures. I merely say that it should not because Taxation has immense costs in government squander and in deadweight costs, both of which disappear were a community to have its government borrow to fund public services. A borrower such as a bank will never call in a loan to repay a depositor seeking their funds. They merely find another lender to substitute for the first. And so shall the community with its lenders, exchanging one for another when calls for repayment arrive. One is wise not to sell an asset yielding a 100% return to pay off a debt on which he pays 5%. The borrower is best to find another lender. And so it shall be with a community of citizens.

With Taxation abolished, public slaves become public bankers, and government is forced to justify everything it does to its perpetual bankers. Any hint of fraud or squander, and heads will role. Otherwise the government will have no lenders and no revenues. So all those politically useful but economically detrimental programs that have arisen over the years will disappear with the result that the costs of government should decrease by half. Federally in the US, the public shall be wealthier by $2 trillion every year. And don’t forget that the deadweight costs of Taxation disappear as well. Now one may labour, save, invest, consume, reduce debt without any consideration of taxes. That should be worth another $2 trillion to the US. So the public will receive $2 trillion in valued government expenditures, $2 trillion added to their wealth by the abolition of worthless government expenditures, and a further $2 trillion in wealth from the removal of the deadweight costs of Taxation for the liability incurred of $2 trillion. That $6 trillion in assets and $2 trillion in liabilities, leaving wealth enhanced by $4 trillion each and every year.

Below is a link to the “Idea in Operation” on my webpage regarding the great increase in wealth with the abolition of Taxation.

Here it is https://www.economart.ca/the-idea-in-operation/

In this exposition, the nation of Canada will create under a borrowing scenario about $3.6 trillion in assets for its residents over a certain period whilst incurring $1.6 trillion in public debts or liabilities, yielding wealth of $2 trillion for its residents. Now whose balance sheet would you rather have, one which has generated $3.6 trillion in assets at the cost of $1.6 trillion in liabilities by borrowing? Or the opposite, $1.6 trillion in assets at the cost of $3.6 trillion in liabilities by taxing?

On public expenditures, all I do is remark that Government will be forced to shed the bad ones, those that raise the liabilities of the community without producing returns surpassing costs. And I only speak of returns, not to the government, but to the community residents, to their assets, incomes, property, etc. We do require a public education system, but we can do without the needless and inherent squander and corruption. So the costs of public education shall decline as expenditures are restricted to worthy endeavours, enriching the citizens with lower costs.

I hope this helps.

Hello Economart.

I included the issue of the proper use of state funding because I feel it is just as important as the source or size of that funding, especially when one is dealing with the possibility of a “flaw” in the theory. I am sure most people would consider any measure to be flawed if it leads inexorably to citizen impoverishment and servitude, the very things that your proposal is supposed to prevent.

However, even if we skip over that issue for the moment, we still must consider my primary argument, which was not acknowledged in your response. In summary, that argument is (1) only profit-making enterprises are reasonable candidates for investment, (2) political bodies, by reason of their regulatory nature, are not profit-making ventures, and (3) if they were to be altered in an attempt to make them profitable to investors, they would fail, either to continue serving the primary function of the state (protection of life, liberty, and property), fail to make a profit, or (more likely) fail to accomplish either one.

If necessary, I stand ready to defend that conclusion and expand the rationale behind it, but I anticipate that you do not need that. Any person with an understanding of human nature and the corrupting temptation of political power can easily imagine how much worse it would be if the additional temptation of economic power were layered on top of that.

The headlines of our present day bear mute testimony to the influence of corporate power creeping into the chambers of government. The corporate state (fascism is its technically correct name) is rearing its ugly head everywhere we look. Take the pharmaceutical industry, for example. Already, these companies have used their economic clout to achieve ”regulatory capture” as they call it. The FDA no longer serves to protect the health of consumers but to protect the profit margins of producers. It would be infinitely worse if we were to give legal sanction to this unholy alliance, which would be the effect of the proposal you have made. Instead of corporations having to bribe politicians, corporate executives and politicians would become one-and-the same!

Profit, cash flow, salaries, perks, and bonuses would quickly outrank almost any consideration for the public benefit. If that isn’t a fatal flaw in the theory, I can’t image what would be.

As stated previously, I am willing (for the moment) to overlook this issue of desirability and stick with the issue of feasibility. On that basis alone, a fascist state cannot function on

a voluntary investment basis. The only way it could produce a profit for investors is by using state compulsion to support monopolistic projects. The final proof of the fatal flaw, therefore, is that your proposal cannot work in a free society because, without coercion, state ventures cannot pay a reasonable return on capital investments; without that, there will be no funding; and without funding, everything fails.

Mr. Griffin,

I did read through your response.

I did deal with the issue you raised in the final paragraph of my initial response. I believe I said that how funds are raised for public expenditures, whether taxed or borrowed, has little bearing on what public expenditures are made, on what one may consider a worthy public expenditure. Much in the way of how a bank or a firm such as IBM raises funds has little bearing on what those funds are used for, as long as returns exceed capital charges and all costs. Do you disagree with my contention?

You make several statements. The first being that only profit-making enterprises are reasonable candidates for investment, the second that political bodies, by reason of their regulatory nature, are not profit-making ventures, and the third that if they were to be altered in an attempt to make them profitable to investors, they would fail, either to continue serving the primary function of the state (protection of life, liberty, and property), fail to make a profit, or (more likely) fail to accomplish either one.

I accept the first with some reservations relating to public expenditures and public finance. It appears that many governments are able to borrow at the lowest interest rates in the land to fund all sorts of public expenditures, of which most one may argue have dubious value and certainly no apparent profit making returns; That the debts incurred by the nation or state only grow with time as I have never seen any such entity reduce those aggregate public debts; That governments of nations possessing sovereign currencies will inflate the supply of money causing inordinate amounts of inflation to mitigate any difficulties arising from a failure to repay those debts that they never do repay and still find ready lenders.

You may argue that nations may tax, which permits their governments to borrow. Well, nations such as Greece or Argentina, armed with the instrument of Taxation, find the rates offered in the financial markets prohibitive, effectively barring them. So to say that possessing the right to commandeer the property of others guarantees public loans appears erroneous. I think that there is an appearance that the right of Taxation guarantees loans, but in truth it is the wealth of a nation and all pertinent factors that decide the procurement of borrowed monies and determine the rates offered. I also did not say that a community is prohibited from having its government tax to raise funds under my proposal. That right still exists. I said that a community WOULD NEVER have its government tax because the financial costs of Taxation are immense and the benefits of Taxation nil. One would never sell an asset producing a 100% return to pay down a debt with a capital charge of 5%. The person would just find another lender. And so shall the community direct its government.

You say that political bodies are not profit making ventures. If this be true, then I must ask why any community would invest as they do in police, fire, garbage, ambulance departments, regulatory bodies, education, roads, health, defence, etc? If the costs of such expenditures yield no returns or profit, then why make them? It would not matter whether the funds were borrowed or taxed. The determination of what constitutes a good public expenditure has nothing to do with how the funds are raised. So why build and maintain roads, maintain public order, educate children? Of what profit is there for a community in performing such deeds?

Just because one does not account the benefits does not mean there are none. Great benefits arise from public expenditures provided they are done well. You mention the FDA. Under a regime of Taxation, the FDA is free to do as it pleases. By having to face the nation, the public, for funds daily, do you believe it shall continue to work in its own interests and those of the firms it regulates. I don’t believe it will. Were it to do so, it would find itself bereft of funds as would many government operations and departments that ignore deliberately their purpose of being.

Imagine a nation that only produces 100 bushels of wheat under a system of big government and punishing taxes. The government takes 50 bushels of wheat and spends 20 on worthy public expenditures and uses the remaining 30 bushels to feed its dependents who perform little or no work, leaving only 50 bushels left for the nation’s producers.

Now imagine that the government can no longer take the nation’s product, that Taxation is abolished and it must now face the nation’s resident lenders to fund all its enterprises. Government expenditures will now drop to a worthy 20 bushels, leaving 80 for the nation’s producers. So erstwhile dependents must now become producers in order to survive. With the abolition of Taxation, all penalties on production cease. The deadweight costs of Taxation disappear. So imagine that the nation now produces 130 bushels of wheat. The produce garnered with the abolition of Taxation, once just 50 bushels, is now 110 bushels. The nation is far wealthier than it was, far more productive, each and every year. Assets created among those that fund government is 60 bushels of wheat plus 20 bushels for public bonds issued or 80 bushels. Liabilty is 20 bushels in bonds, or claims against the assets of residents, borrowed to fund public expenditures. The increase in wealth is 60 bushels. Should you add interest, you add it to both sides leaving wealth unaltered. Reduce the debt, and both assets and liabilities reduce leaving wealth unaltered.

Is there no profit in this undertaking? Would you not lend to such a profitable enterprise? By incurring these debts of 20 bushels, the people are left not with 50 bushels to share in, but rather 110 bushels; That the public credit is enhanced, not diminished. The people are enriched, not impoverished. That the public liberated from a harsh servitude under Taxation now command government.

How will you conduct this borrowing from the citizenry of Manitoba? Where will you sell bonds? Will you sell bonds for specific projects? For instance will there be highway 256 extension bonds and Bishop Grandin resurfacing bonds or Street maintenance bonds or can you purchase a combination of any of these and more. How will you get consensus on expenditures? Do you have some direct loan and interest idea? Will it be fund raising? Will the government have to sell us on the expenditure before there is a loan or sale of bonds effected.

Presently, we are suffering under the pressures from Mayor (photo-op) Bowman to fund a plethora of Aboriginal (woe) residential school remembrance and celebratory projects. I know these are city projects, but photo-op is very adept at getting the province to pay for city nonsense. For instance the province is funding a community project at $200,000 x 3 years = $600,000 which is using “workers already in the community” to implement. Seems to me there is already a program. Where is this money going. I haven’t approached the province to ask yet because I found this on the Wpg Police site and they won’t talk.

Is the idea that, if a project is redundant or unnecessary, no one will buy bonds to fund it, so it will be discarded. Or is it that the province won’t even consider this in the first place because it cannot be supported by a viable business plan and therefore won’t be accepted by Manitobans. I want to be on the ground in decisions regarding big and small ticket expenditures. There are no drop-in-the-bucket expenditures as far as I’m concerned. All expenditures are important, they all cost, they all add-up.

Greetings,

The Government of Manitoba shall sell bonds strictly to the people of Manitoba, to whomever wishes to lend money, by wading into the financial markets with the interest rate settled upon by the forces of supply and demand. The bonds probably will be sold for general purposes, though the Government may wish to sell bonds for some specific projects as a test of popularity. If financing is successful at an acceptable interest rate, the project goes ahead.

The worth of a project should be decided by cost and benefit analysis, quite an alien concept in public expenditure today. There is no measure of a good government expenditure. One is never sure that the funds expended generate returns surpassing all costs. To divert large sums of money, labour and materials in order to dig holes in the morning and fill them up in the afternoon generates great costs without any return to the citizens of the jurisdiction. Using the same funds to train electrical engineers or plumbers will generate some return. So the Manitoba Party will endeavour to ensure that funds, diverted from otherwise productive purposes, shall generate returns exceeding all costs.

Does that answer your question?

Regards,

Economart

The problem with “The worth of a project should be decided by cost and benefit analysis”, and therefore selling bonds for a specific project is, in the case of building a bridge (or underpass) to either improve traffic flow, or provide “flood proof access” to an isolated, or semi-isolated community, only going to go forward if there are enough people capable of paying for the entire cost of that project. In the example, if you want to fund a project to build an underpass on Waverly, there is direct benefit to a neighbourhood and surrounding area for say 200,000 people. The cost of the project is say $2 million, which equates to $10.00 per person, however building a bridge that would provide year-round access (or maintain access during high water events) to an otherwise isolated community of 2000 at a cost that would be similar, but even at only $1 million, would then be $500. SO, that means that projects benefiting big population centres would have a much greater chance of proceeding, or projects benefiting wealthier areas of the city would be funded over poorer areas.

Greetings Chad,

I did read through your thoughtful email. Very good questions.

It is cost and benefit analysis. The factors involved are many. One may build many different bridges to service communities. I would expect that the cost of a bridge to service a small community of 2000 in the north need not be as high as one servicing a community of 200,000. It depends upon the volume of traffic or goods coming across and the frequency of that traffic as well as the ground and weather conditions. In a smaller community, the value of the real estate or property in the community and the need to live in a remote area where supplies are intermittent and food scarce should also form part of the analysis. Why are they living so distant from good and reliable sources of supply? Are their alternatives routes of entry via water, rail, air, and land? Are their alternative methods of providing food and shelter? If its a remote mine that justifies the cost, then fine. But maybe the mine owner should build the bridge.