Deterrence of Taxation

Taxation in all its forms fosters a discernible reluctance to engage in worthy economic undertakings. Taxation is by nature a penalty or fine. The intention with its employment should be to discourage or prevent, not to encourage or induce. Its utility is prominent in penalizing those who excessively speed, defraud the naive, violate commercial contracts, and transgress the laws of property. Yet, Taxation has become the principle instrument by which a community or nation raises funds for public endeavors. The explanation for its destructive ubiquity must be as devoid of reason as the statements of malevolent feminist activists and their adherents.

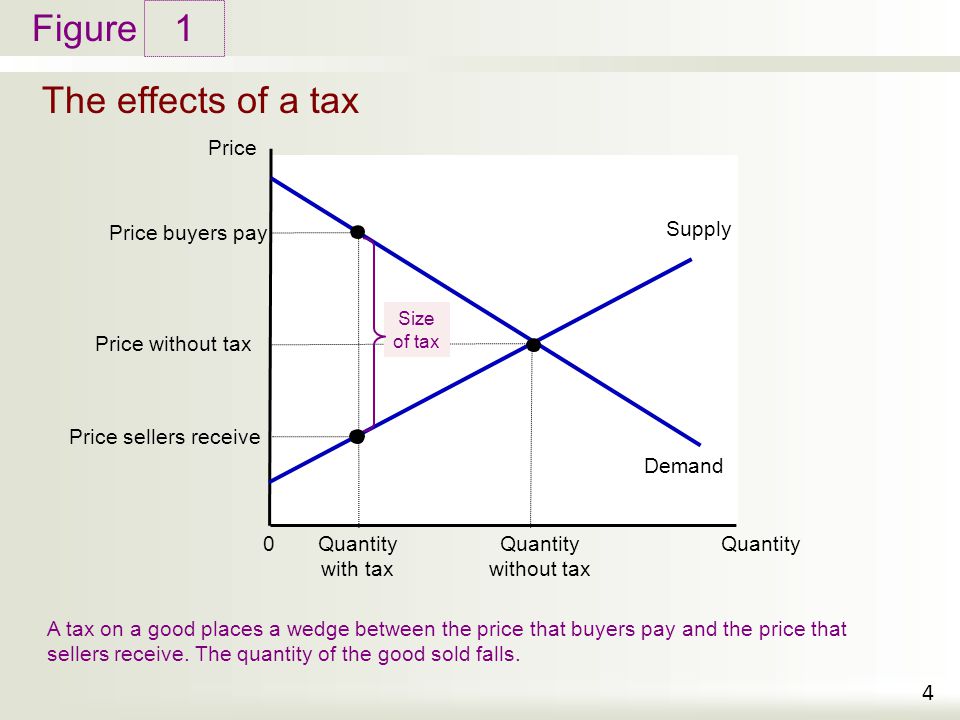

Valued and common economic activities such as the purchase of food or the offering of one’s labour face ceaseless surcharge or penalty. One must repeatedly evaluate whether the diminished remuneration of labour justifies the undertaking or the augmented price of a good justifies its expense. Deprived of the full proceeds of one’s labour or industry, workers become hesitant to exert themselves and companies reluctant to produce when confiscation of returns are deliberated and assessed. Idleness is preferred to activity, limiting capacity, curtailing wealth, encouraging poverty and all its noxious ills among large fractions of a community’s population.

When exactions surpass grievous, a certain element of the public, innately rebellious or wearied by severe imposition, desert the jurisdiction of legitimate Taxation altogether, conducting business and affairs liberated and concealed from the commandeering hands of Government. Presently, innumerable businesses, especially of diminutive size, and wage earners operate accordingly, with some opinions condemnatory and others envious of the bold scofflaws. They illegally, but lucratively conceal income from the predatory tax collector. As Taxation is exempt from their costs, they are able to manipulate the prices charged for goods much to the detriment of rival businesses that justly and diligently adhere to the manifold and abstruse rules of Taxation no matter how exacting. Such distortions and inequities in the marketplace only aggravate and multiply when Taxation levels escalate.

Others persons, marked by the same prejudice, depart the nation or remit assets beyond the bounds of the Taxation authority. Each year this and many nations lose a number of individuals to more advantageous and clement environments of Taxation. These persons frequently possess in abundance expertise and talent, qualities zealously cultivated in civilized nations and eagerly chased away. Resentful of an authority that demands exorbitant amounts of the rewards of their labour and cunning, they merrily proceed to more hospitable lands. Of those unwilling to leave the native soil, many unflinchingly transfer financial assets out of the country to nations that offer refuge or relief from ill-considered Taxation policies. These evasive actions deprive nations of the best among them, the most productive of the land.

Preparation of tax forms and adherence to the rules of innumerable jurisdictions demand precious knowledge and deft manipulation, greatly inflating the administrative costs of commercial enterprises which are then reflected in the price of goods sold. How much time is expended slowly and punctiliously collecting the varied information and funds? How much time to ensure forms are satisfactorily completed for the diverse administrations of numerous levels of government throughout the world?

And what of the outlays for countless persons employed in a battalion of government departments engaged in receiving and processing the assorted forms and documents. What must be the sum of remuneration of those developing and implementing new Taxation policies and law, enforcing existing policies, adjudicating disputes, analyzing diverse forms, and collecting various taxes?

Through the years, the rules and laws of Taxation have become exceedingly complex such that even those employed by the appointed authority find frequent disagreement among their colleagues over seemingly plain issues. The complexities have arisen from two principal quarters.

Firstly, during robust economic periods, the government, desirous to dispense the great quantities of money deluging its financial accounts and to appear concerned and active to an unconcerned and prospering electorate, hastily implement a range of measures. These measures, not infrequently consisting of tax incentives, achieve little and accumulate inexorably. Rules and their attendant regulations soon overlap, interfere with, and often counteract one another. Inevitably, the multitude of discrepant policies and laws confound those most expert in the field including those employed by the appointed government body. Programs dedicated to fulfilling the most bankrupt of ends continue without abatement, even during recessionary catastrophe.

Secondly, the wealthy and corporate interests possess a disproportionately large amount of the wealth of the nation. Affluent groups and firms will direct investment from within to without or order their financial affairs to ease the claims of extortionate Taxation. They are inclined to hire knowledgeable, shrewd and expensive counselors to protect their interests. For the majority of people such advice and assistance is financially prohibitive. Extraordinary efforts are made to conceal income or evade tax by planning and implementing the most elaborate of intrigues. Legal experts exploit obscurities in law for to establish bewildering schemes of concealment. They avail themselves of states or countries that have less or no taxation. They solicit politicians with persuasive and not infrequently, compensatory pleas for exclusions and variances in new or existing laws and policies. With success in devising overtly evasive operations the government and its leaders are compelled to create more complicated and subtle policy, creating a need for more lucrative pleas and consultations that hopefully yield enriching or favourable judgments and exemptions.

Of the masses a noticeable fraction garner slight reductions in tax remissions by shaving their enforced contributions here and there, exaggerating certain claims or liabilities, and omitting certain revenues obtained through irregular means. With augmented imposition, such pecuniary misdemeanors flourish.

Revenues to fund public projects and services accrue through impersonally applied rates and charges upon property, wealth, and income. The usage of government services has little bearing upon an individual’s contribution to the costs of those services. If a family comprise 1 school age child, then it contributes funds to education by a measure wholly unrelated to the demands it places upon the system of education. A family of 10 school age children and the family of one living within the same vicinity could and very often do contribute comparatively similar amounts of money to the same school district. An individual repeatedly visiting a public hospital may contribute an amount equivalent to that of an individual with similar financial circumstances rarely visiting the same hospital. A person or business, conscientiously re-cycling refuse, placing one bag of garbage for pick-up, pays a rate equivalent to a similar firm eschewing re-cycling and submitting 10 bags.

Attempts to balance the discrepancy by implementing a system of payment proportioned to use, in conjunction with Taxation, would meet and has met with great resistance. A hostile majority merely view it as a supplementary tax. The funds for the provision of services have already been collected, allocated, and dispensed. It is well known that government functionaries are loath to remit any savings from operations lest it curtail future department revenues. Consequently, they will expend conserved funds on ventures, necessary or frivolous. Bereft of a mechanism to ensure the savings culled from supplementary charges convert to lower tax rates, the public would rarely enjoy the largesse created.

Without the deterrent of elevated cost to curb excessive use of government resources by individual or enterprise, the inequities and injustices inherent in Taxation proliferate, aggravating the waste of public monies and undermining any profitable means of distributive control.

Lastly, I am certain that, with the assistance of the reader, the list of disadvantages could expand exponentially.

One may genuinely wonder at the weighty burden Taxation places upon the industrious nature of Man and how much it must remorselessly strip away from the economies and wealth of the people of nations and of the world! An accounting of the breadth of its ruinous and corrosive influence must be impossible. It is a known to all that Taxation is a relentless scourge, forever impairing and impeding Man’s intellectual treasures and their fruitful employment in the betterment of his wretched condition. Without this virulent scourge, Man’s condition can only improve.